As early as the Civil War era – before Washington was a state and Seattle became a city – white settlers promoted segregation across the Pacific Northwest. Seattle officials in 1865 passed an ordinance calling for the removal of Native Americans from the town unless hired and housed by Caucasians as their help.

This, in effect, marked the beginnings of our city’s race-based housing discrimination, established by one group of citizens against others. The laws forbade the very people whose ancestors had occupied the land for thousands of years from enjoying the benefits of living freely within a growing community.

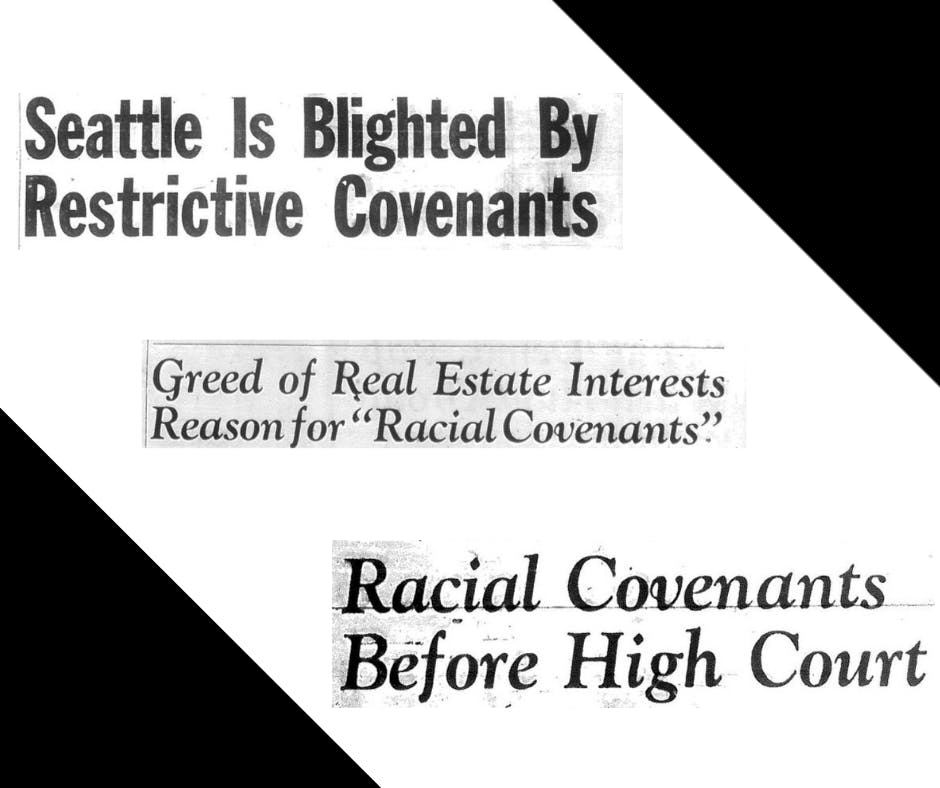

The ban on Indigenous peoples was lifted in 1869 when Seattle was incorporated, but bias remained a strong undercurrent through the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Among the more pronounced acts of discrimination were written into property documents that prohibited people of color from residing in certain surroundings such as on a street or in a property development.

These race-based restrictions could be found throughout Western Washington starting in the early 1900s and even flourished after a 1926 U.S. Supreme Court decision ruled the covenants as enforceable contracts. The thinking then was that, by including the language white owners could protect property values. A violation of the rules could lead to both the eviction of the new property owner and legal consequences against the seller.

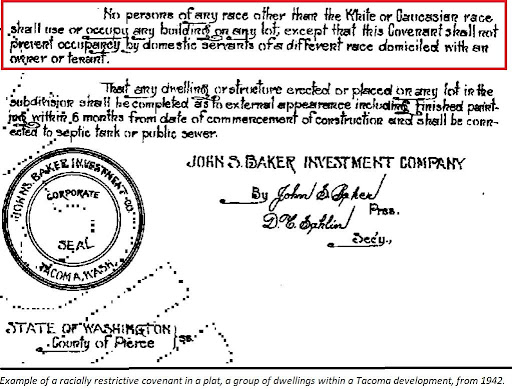

The restrictions were included in a variety of land-ownership documents – Homeowners Association bylaws, community documents known as Conditions, Covenants and Restrictions, deeds of sale, property titles and on plat maps for new subdivisions (below). Once a covenant was recorded by the county, the rule was binding and applied to all properties linked to the document for all future owners in perpetuity (known as “running with the land.”).

It wasn’t until 1948 that the Supreme Court essentially reversed its earlier ruling and found property-ownership covenants based on race to be unenforceable. However, housing discrimination itself was not enforced until Congress passed the Fair Housing Act in 1968 – only days after the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. A year later, Washington state passed a law to invalidate race-based discrimination in real estate activity including the use of racial covenants.

In a month in which America celebrates the birth of the great civil rights leader, we are witness to a slow but sure removal of race-based restrictions from the region’s property documents. Even though the language is no longer legal, the words carry a stigma stemming from the Jim Crow era that should be extinguished from present-day records.

It has taken a collective effort – from government leaders, racial justice activists, Realtor associations and academia – to get there. John L. Scott Real Estate has been an active participant in this effort. The brokerage, which began more than 90 years ago in a segregated Seattle, today is partnering with Amazon Web Services to help expedite the document search process and notify affected property owners.

Washington state lawmakers have passed legislation to streamline the act of striking the language from property-ownership documents. In 2021, the legislature approved a bill authorizing teams of researchers from the University of Washington (UW) and Eastern Washington University to pore over hundreds of thousands of files for the restrictive entries.

Part of the legislation reads: “The existence of racial, religious, or ethnic-based property restrictions or covenants on a deed … is like having a monument to racism on that property and is repugnant to the tenets of equality …. [and] such restrictions and covenants may cause mental anguish and tarnish a property owner’s sense of ownership in the property because the owner feels as though they have participated in a racist act themselves.”

More than 40,000 properties with racial restrictions have been identified – and those are just preliminary results from four Puget Sound area counties. More than 30,000 of the properties – including 342 subdivisions – are in King County. Pierce and Snohomish counties each have about 4,000 examples of racial covenants, so far, and Thurston County has around 1600.

Millions of pages of property documents remain unchecked, including many only available on microfilm, in bound volumes or within other non-digitized formats. When a property is identified, owners are notified and guidance is provided to eliminate the offensive language if they wish to do so.

To raise awareness of this matter, the Seller Disclosure Statement now includes a notice to buyers and sellers about the process to remove discriminatory covenants. The disclosure statement is completed by the owner and shared with buyers when the home is listed for sale.

The local effort to remove racist language from property documents dates to 2005 as part of a project at UW’s History Department. It marked the first such movement in a major U.S. metropolitan region and has since inspired similar efforts across the country.

In addition to correcting a long-standing real estate wrong, the effects of ring-fencing properties to the exclusion of others can have a significant financial impact. Blacks, Asians, Hispanics, Native Americans and other groups can lose out on the wealth-generation potential of homeownership when prohibited from communities.

A long-term result: Households of color typically have lower savings and are less likely to benefit from intergenerational transfers of wealth than white households, a report from the Federal Reserve concluded. This tends to lead to households of color possessing lower credit scores than similar white households, according to Urban Institute research.

Today across the U.S., 47% of households headed by people of color own their home compared with 72% of white households, according to U.S. Census data that demonstrate the long-term effects of discrimination.

The path to removing racist language from property documents is welcome. It is this action – and others aimed at bringing homeownership opportunities to all – that would have likely reassured Dr. King his efforts and sacrifices of more than a half-century ago did not go in vain.

RESOURCES AND RELATED STORIES

History of Racial Restrictive Covenants in Seattle

Racial Restrictions Found in King County Communities

Driving Change – Restrictive Covenants Modifications

The Importance of Fair Housing in Our Society and for Seattle

A Call to Erase an Ugly Part of Our Local History and Move Forward as One

Seattle’s Connection to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr., Housing Inequality and the ‘Missing Middle’