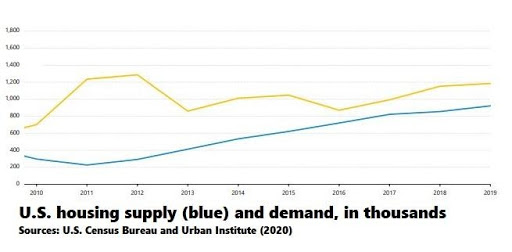

You have read it here and probably elsewhere: Our housing inventory is at or near historic lows and efforts to reverse course has been difficult to accomplish, prompting stiff competition for those homes on the market.

Laurie Goodman, Vice President of housing finance policy at the Urban Institute, describes the U.S. housing shortage a “crisis.” The Institute has found a shortfall since 2009 of roughly 350,000 homes per year caused by an under production of new homes and other factors. The result, Goodman told Realtor® Magazine will be “a huge deficit in housing over the next decade.”

Despite the seemingly endless housing deficit, there are glimmers of hope and plenty of fresh ideas to try and help get us out of this hole. In fact, a survey of Realtors® across all 50 states last year surfaced some bold, innovative ways to address housing shortages:

- The Vail (Ariz.) Unified School District supported its teachers by constructing a tiny home village on land purchased by the district to help educators stay in the communities where they teach.

- Municipalities across Maine are financing affordable housing, public infrastructure improvements and social services for residents through a state tax program that offers communities flexible financing tools.

- First-time buyers in Colorado can establish a tax-free, home-purchase savings account to help cover closing costs. The state forgoes collecting interest and capital-gains taxes for the life of ownership. At least four other states have similar programs in place and there are proposals to enact a matching-fund component for companies to contribute to their employees’ home-saving goals.

Closer to home, Microsoft and Amazon, along with philanthropic organizations, have combined to pour more than a half-billion dollars into local efforts to address affordable housing (and homelessness), even as Seattle City Council approved an approximate $200 million-a-year tax package on bigger corporations (unlike the unpopular “head tax” proposal, this time it’s only against the highest-paid employees) to primarily fund the buying and building of low-income housing. (The 7-2 vote in July 2020 would allow the council to override a veto from the mayor who is weighing alternatives.)

At this point, the city reports more than 5,500 affordable housing units will come online by 2023, adding to the 17,600 count – with more on the way from this new measure. But many of these places are rentals and do not appear to directly help people get on the property ladder.

Housing authorities in Seattle and King County are filling a needs gap through housing assistance programs that find affordable homes in neighborhoods deemed to offer more opportunities for personal and professional growth. But there is more to be done – much more.

In 2019, the city council eased restrictions on accessory dwelling units (ADUs) – either as part of an existing home or on the property (known as detached accessory units, or DADUs). There are about 2700 of these units permitted or constructed in the city – still only 2% of Seattle’s roughly 135,000 single-family-zoned lots. And, again, these are typically rental units – not homes for purchase.

Many people in the know claim the practice of building on city land is onerous and time-consuming. The Seattle Times (login may be required) noted in 2019 that developments requiring design review averaged 519 days in the pipeline before approval, up from 316 only 5 years earlier. Forbes even covered this topic earlier in the year, reporting:

The city regulates land use through the Building Code, Electrical Code, Energy Code, Fire Code, Mechanical Code, Plumbing Code, and Residential Code. The city requires permits for almost all construction and repairs. It also has extensive and complex zoning regulations regarding what can be built and where. This is on top of state and federal regulations.

Overcoming this labyrinth of permitting – by removing some requirements or consolidating others – is a critical step to unlocking the doors to more housing. Even the mayor, Jenny Durkan, acknowledged this when introducing the new ADU law, saying: “We can address the serious regulatory, financial and permitting challenges for backyard cottages.”

Also established in 2019, the Mandatory Housing Affordability law requires new residential development to include a percentage of affordable homes by either providing rent- or income-restricted housing on-site or making a payment to support construction of affordable housing. This was implemented while also changing zoning to allow larger development and greater density in neighborhoods from the University District to the International District – all in an effort to generate multi-family development close to major transit corridors and Link light rail expansion.

These are all steps in the right direction but so far measured in small victories and not major breakthroughs. Affordable housing does not just happen and addressing the issue requires a high volume of inventory to balance supply with demand.

State liability laws were also relaxed to help spark new condo construction across the region. Previously, Homeowners Associations could sue builders for almost any defect, a situation that led developers to build more apartment projects and townhomes. We are still a long way away from seeing enough affordable condo homes, begging the question, Why don’t builders convert apartments to condos? The answer, so far, is that the revised laws still make building condos too risky for many local developers.

Without a sharp increase in inventory – such as apartment conversions to condos – the shortages will continue. And the lack of purchase options result in higher home prices today and likely tomorrow.

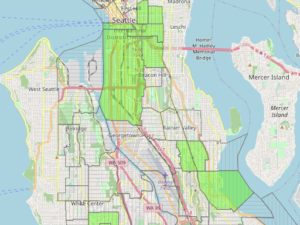

The U. S. opportunity zone program, established in 2017, offers tax breaks to investors who purchase and improve property in economically distressed areas. Investors can reduce or postpone taxes on their profits from stocks, businesses or partnerships by reinvesting those funds into communities needing improvement – and hold those investments for at least 10 years. There are several opportunity zones in Seattle (located in green) and about 8,700 areas nationwide. In fact, most experts believe these areas can expect a surge in people moving there once reinvestment and gentrification takes place. The process of creating affordable housing – from acquiring a site for construction to handing off keys to the home – takes seven years on average nationally, prompting the need to accelerate the timeline.

While constructing new homes is critical, providing access to funds to help those potential buyers in need is also important to addressing an imbalance across the social and economic spectrum. Saving for a home is the most challenging hurdle to clear for buyers. There are many programs in Washington state that can help them with both their earnest-money deposits and down payments – and many of these opportunities are grants.

Clearly more can be achieved with the help of financial institutions and federal regulators to prop up disadvantaged people. Some believe the Federal Housing Administration, which has been critically important to helping first-time buyers and minority households, should shift more money to strengthen the FHA program to help reduce mortgage insurance premiums and monthly payments. Lenders, too, could try to be more lenient with their credit scoring models to, for example, include rent and utility-bill payments as part of a person’s financial history to better demonstrate an applicant’s fiscal responsibility.

This is a massive issue with many moving parts – but, be sure, we will get it done. It just takes time.